Quality, Rarity and Value, Pricing the Crème de la crème of Gems Part II

By Richard W. Wise

© 2006

Wildcard Properties:

Some gem varieties also sport particular qualities, what I shall call wildcard properties that affect one or more of The Four Cs of Connoisseurship (color, cut clarity, crystal) and will dramatically effect the price of a gem particularly in the upper reaches of quality. The following is a list of wildcard properties, their affects and effects:

Colorless Diamond; (Crystal): Diamonds reputedly from the old Golconda mines located in northwestern India that exhibit a particularly high degr ee of transparency. The Golconda fields were the primary source of diamonds from antiquity until approximately 1725 and Golconda stones sometimes come up at auction. Gems with this property are also referred to as super-ds, something of a misnomer because they are really super-transparent and may be found in lower color grades.

ee of transparency. The Golconda fields were the primary source of diamonds from antiquity until approximately 1725 and Golconda stones sometimes come up at auction. Gems with this property are also referred to as super-ds, something of a misnomer because they are really super-transparent and may be found in lower color grades.

Emerald; (Crystal): They are called old mine stones; emeralds mined in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries at Colombia’s emerald mines as well as particularly fine gems from Pakistan and Afghanistan that leaked into the Indian market during that period.

Oddly enough green sapphire (Oriental Emerald) was so deeply entrenched in the European psyche that the lovely verdant true emeralds of Colombia, stones from mines at Muzo and Chivor that were pried from native hands beginning around 1580, were not well accepted in Europe and were transshipped to India via the Philippines. The Indian Maharajas knew a beautiful stone when they saw one and paid princely sums for Colombian gems.

There is controversy about what constitutes an old mine stone; some experts maintain it is a pure green hue without secondary hues but it is in fact a honey like quality of transparency also called gota de aceite or “drop of oil”.

I had the privilege of comparing several of these old mine gems. This quality can be s

een when comparing a very fine crystalline emerald mined recently with one of these old mine gems. They do indeed exhibit a thick crystalline quality reminiscent of light passing through honey or oil.

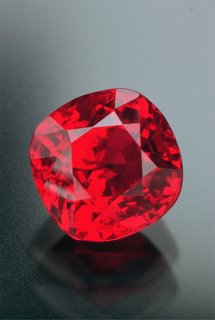

Ruby: Mogok Origin: (Color):

“At a carat there is a price. At a carat and one half that price doubles. At two carats the price triples…at six carats there is no price.”

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, 1688

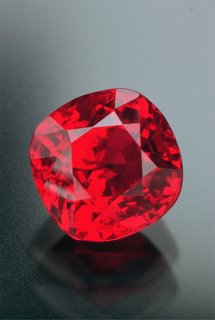

In 2005 a world record price for ruby was set when a private client from Asia paid the fabulous price of $2.2 million or $274,6

56 per carat for an 8.01 carat oval ge

m. This bested the previous record of $228,252/ct. set back in 1988 with a 15.97-ct. gemstone. In February 15, 2006 Christies St. Moritz shattered that record selling a 8.65 carat cushion shaped ruby to a dealer for the final hammer price of $3.6 million or $425,000 per carat, nearly double the record set just one year before.

Christies St. Moritz shattered that record selling a 8.65 carat cushion shaped ruby to a dealer for the final hammer price of $3.6 million or $425,000 per carat, nearly double the record set just one year before.

What makes Burma ruby so special is a normally invisible quality of ultraviolet fluorescence, rubies from locations in Thailand, which was the ruby standard bearer in the years between the closing of

Burma in 1962 and the discovery of the new Burma ruby deposits at Mong Hsu in the early 90s, have concentrations of iron that quench the gem’s natural fluorescence. In Burma type ruby, found at geologically simila

r locations in Burma (Mogok) (Namya), Vietnam, Pakistan and Afghanistan, some ultraviolet emissions fall into the visible red (at 692.8 and 694.2 nm). The red body color is supercharged by red fluorescence. Vietnamese gems are particularly strong in this quality.

Some dealers are beginning to discriminate between g

ems produced in the Mogok Valley and those from other sources. It is sometimes possible, by inclusion study to separate Mogok stones from other Burma-type rubies from Pakistan, Afghanistan and other parts of Burma (Namya and Mong Hsu). Taking the cue from Emerald, ruby from the original source are referred to as old mine.

Blue Sapphire; (Crystal): Kashmir stones, those mined on one side of a rocky hillock in the Indian State of Kashmir f

amed for their fine color and the quality of transparency or crystal, that is variously described as a velvety, milky, misty, fuzzy glow. This affect is the result of light passing through myriads of extremely small inclusions called, variously flour, sugar or snow. Like the Starship Enterprise passing through an asteroid belt, light colliding with these tiny particles results in the signature fuzziness in the Kashmir gems. Kashmir sapphire from the original deposit was essentially mined out in the 30s and though some continues to dribble out from adjacent areas, they rarely show the quality of gems from the original mine.

The image (left) shows a Kashmir sapphire of indifferent color with a very distinctive velvety glow: The affect is often difficult to capture in an image. The image (below left) shows a Kasmir sapphire in its full glory, fine color and glow. (image courtesy Pala International)

Padparadscha Sapphire; (Color; saturation/Crystal): Speaking of padparadscha (see Grading the creme, Part I); though some experts insist upon Sri Lankan (Ceylon) origin, geography (gratefully) plays almost no role in pricing. Padparadscha is all about color. Which hue should dominate and what are the preferred mixtures of pink and orange? This remains undefined. However, it is safe to say that a true padparadscha has significant percentages of each hue. Although labs are now calling gems with even a trace of one or the other, orange

stones with less than 20% pink and pink stones without similar percentage of orange secondary hue should not be considered. The gem pictured ( right) is a padparadscha sapphire from Malawi, West Africa.

Some padparadscha’s will exhibit a strong orangy fluorescence under ultraviolet. Like the rubies of Burma, this quality tends to supercharge and sometimes overcharge the

saturation of color in the gem. To much fluorescence may overcharge, that is, reduce the transparency or crystal of the gem. Moderate orange fluorescence can be a plus though one not truly recognized or quantified by the market.

Paraiba Tourmaline (Color; saturation)

In the late 1980s a new type of tourmaline was found in the Brazilian state of Paraiba hard up against the border of Rio Grande do Sul. These unusual tourmalines had trace elements of copper that endowed the best of these gems with an intense neon-like saturation. What we call color is scientifically divided into three components hue, saturation and tone, hue is the term for color as we normally use that term and saturation refers to the brightness or intensity of the hue. (see Secrets Of The Gem Trade Chapter 2) International orange is an example of a particularly saturated hue.

The best of these copper colored beauties are a medium toned Caribbean Blue, a visually pure highly saturated blue similar to the color of the shallow waters of the Caribbean Sea that is considered the finest color in this gem. The gems of Paraiba became the gemstone success story of the Twentieth Century as the prices for these stones escalated from a few hundred dollars a carat into the tens of thousands.

Cupriian tourmaline from Paraiba pretty much had the market to itself until 2001 when Cuprite tourmaline in northwest Nigeria and just lately similar gems in Mozambique. Dealers working with these stones naturally wanted to cash in on the Brazilian gem’s market cache and call these gems Paraiba. This has sparked a lot of controversy in the gem trade. In February 2006 the Gemstone Industry Laboratory Conference (GILC), a committee made up of representatives of most of the leading labs met and decided that they would use the term Paraiba to describe this variety of tourmaline regardless of its source.

To be continued...

Interested in reading more about real life adventures in the gem trade?  Follow me on gem buying adventures in the exotic entrepots of Burma and East Africa. Visit the gem fields of Austrailia and Brazil. 120 photographs including some of the world's most famous gems. Consider my book: Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones. Now only $39.95. You can read a couple of chapters and order online: www.secretsofthegemtrade.com.

Follow me on gem buying adventures in the exotic entrepots of Burma and East Africa. Visit the gem fields of Austrailia and Brazil. 120 photographs including some of the world's most famous gems. Consider my book: Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones. Now only $39.95. You can read a couple of chapters and order online: www.secretsofthegemtrade.com.

Buy it on Amazon: www.amazon.com

Mozambique tourmaline controversy continues...

Mozambique tourmaline controversy continues...